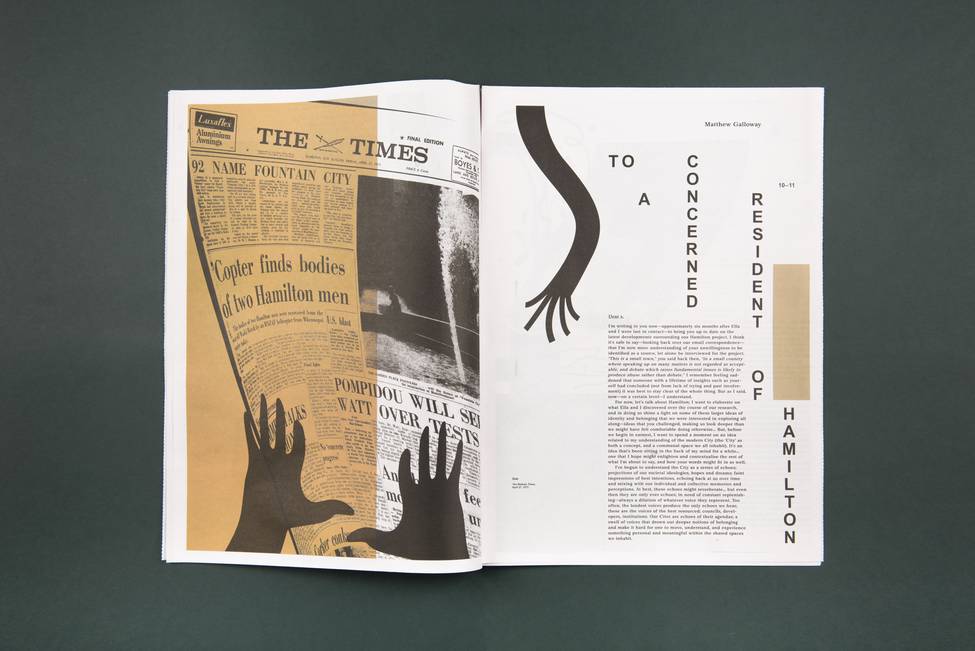

To a Concerned Resident of Hamilton

This essay first appeared in the publication Speaking Places: Hamilton 2015, edited and designed by Ella Sutherland and myself. The Speaking Places series seeks to question how graphic design might offer alternative perspectives; drawing upon historical, cultural and social precedents whilst also claiming its own identity as an autonomous form. In this instance, the project focuses on the city of Hamilton, NZ, and it's forgotten identity 'Hamilton: the Fountain City'. The publication also turns in on itself, discussing the failed public art commission it was originally intended for.

Dear x

I’m writing to you now—approximately six months after Ella and I were last in contact—to bring you up to date on the latest developments surrounding our Hamilton project. I think it’s safe to say—looking back over our email correspondence—that I’m now more understanding of your unwillingness to be identified as a source, let alone be interviewed for the project. “This is a small town,” you said back then, “in a small country where speaking up on many matters is not regarded as acceptable, and debate which raises fundamental issues is likely to produce abuse rather than debate.” I remember feeling saddened that someone with a lifetime of insights such as yourself had concluded (not from lack of trying and past involvement) it was best to stay clear of the whole thing. But as I said, now—on a certain level—I understand.

For now, let’s talk about Hamilton; I want to elaborate on what Ella and I discovered over the course of our research, and in doing so shine a light on some of these larger ideas of identity and belonging that we were interested in exploring all along—ideas that you challenged, making us look deeper than we might have felt comfortable doing otherwise… But, before we begin in earnest, I want to spend a moment on an idea related to my understanding of the modern City (the ‘City’ as both a concept, and a communal space we all inhabit). It’s an idea that’s been sitting in the back of my mind for a while… one that I hope might enlighten and contextualise the rest of what I’m about to say, and how your words might fit in as well.

I’ve begun to understand the City as a series of echoes; projections of our societal ideologies, hopes and dreams; faint impressions of best intentions, echoing back at us over time and mixing with our individual and collective memories and perceptions. At best, these echoes might reverberate… but even then they are only ever echoes; in need of constant replenishing—always a dilution of whatever voice they represent. Too often, the loudest voices produce the only echoes we hear; these are the voices of the best resourced; councils, developers, institutions. Our Cites are echoes of their agendas; a swell of voices that drown out deeper notions of belonging and make it hard for one to move, understand, and experience something personal and meaningful within the shared spaces we inhabit.

Like any other city, Hamilton exists as an outworking of this idea; a case-study amongst many other case-studies just like it. I feel like what we were really trying to achieve through our project was to listen to the echoes of Hamilton; as a way to speak to residents of the city such as yourself, and also critique the general ideals of the City as a concept; a concept upheld and adhered to in Hamilton, as much as anywhere. In order to examine these ideas, I want to discuss a certain moment in Hamilton’s history; a moment of memorialising time, and assertion of identity. The echoes of this moment still exist, if you know where to find them.

*****

On the evening of 1 September, 1978, local dignitaries and residents of Hamilton, New Zealand, gathered in a small park out the back of Founders Theatre to officially open the Centennial Fountain—a $90,000 memorial to the “city’s first century.” Mayor Rod Janson spoke, stating that; “a city, obliged to finance a myriad of services, could sometimes afford to put money towards an object of beauty,”1 he then gave a signal, at which point the Centennial Fountain burst to life—a display of water and floodlights—delighting the crowd with what was described as a “shower of golden light.”

The Centennial Fountain was the culmination of a five year long project to provide a jewel in the crown of Hamilton’s new identity—“Hamilton – The Fountain City”—which was adopted after a competition initiated by a local retail store asked residents to come up with a new slogan for the city.

The 1973 competition yielded over 8000 suggestions for a new slogan, of those 8000, 92 featured fountains, or fountain-themed ideas… but why? As stated in news articles from the time, Hamilton did not have any fountains of particular interest or notoriety (a fountain in the central location of Garden Place the only one that came close). In an article from the Waikato Times in 1974, then New Zealand Founder’s Society Waikato President G.B Batt stated of the proposed Centenary Fountain:

“We call Hamilton ‘the Fountain City’, but it doesn’t have a really good fountain. This would give a soul to the city.”2

Which begs the question; is a soul something you can simply fabricate, drop into the ground, connect to the water supply and switch on? What did this imposed identity say about both Hamilton’s view of itself, and the message it intended to send to the outside world? What representational powers did the idea of a fountain hold over Hamiltonians? A chance to position the city in some new, alternate light by providing some source of inward and outward definition of place?

These questions remind me of something Kevin Lynch said in his book The Image of the City regarding how a city might try and define itself through land marks such as the Centennial Fountain. Landmarks act as central figures within a confusing landscape; they guide our pathway through a city, they engender a sense of belonging and order and signify what is considered of local importance:

Like any good framework, such a structure gives the individual a possibility of choice and a starting point for the acquisition of further information. A clear image of the surroundings is thus a useful basis for individual growth.3

But how does this idea apply to an urban branding strategy based around the introduction of a fabricated image? In the urban environment of Hamilton, the fountain is an introduced species, imposed on the landscape, at odds with the existing structure. Lynch goes on:

A striking landscape is the skeleton upon which many early civilisations erected their socially important myths...4

What does it say about Hamilton that, when memorialising their first century as an independent municipality, they felt they had to fabricate such a myth as ‘The City of Fountains’?

*****

To answer this question, I want to return to your words:

Underlying much (most?) New Zealand cultural production is anxiety about “belonging”—this is a Pakeha articulation of legitimacy.

Could this be the underlying sentiment at play when the soul was conjured as a metaphor? It’s as if the dignitaries of the time believed that a sense of belonging and identity could be articulated through one grand civic gesture, while in turn sweeping any deeper notions of belonging (or lack thereof) under the rug.

Like two sides of a coin—in the context of the City—‘belonging’ looks inward; to the residents of a place, and their very subjective, intimate perceptions of that place, while ‘identity’ might more readily be associated with how a place projects an image of itself to the outside world. Both ‘belonging’ and ‘identity’ are entangled with the notion of a soul; an inner substance and the outward appearance informed by that substance. But neither can be fabricated; certainly not on a civic level, and definitely not at the behest of more pertinent local imagery and histories—as you went on to point out:

…these are confiscated lands, and that is not often or deeply acknowledged. Thus people deny a history which did not just happen then, but continues, and ramifies into current lives (…) Whether the city is ‘cow town’ or ‘fountain city’ or ‘garden city’ or whatever else is about superficialities: these are distractions, or more than distractions: ways of avoiding central issues of identity.

Given this context, it’s funny to think how often the words ‘branding’ and ‘identity’ are used interchangeably, when really they are opposites. To brand is to stamp something with a mark; it is a very shallow exercise in identifying ownership. A brand may be crossed out or replaced: rebranded. But an identity is something much deeper—infact in this instance identity could be interchangeable with ‘soul’—it is interwoven into the very fabric of a place or product. It can’t be fabricated… but as you point out, it can be left unacknowledged, or be covered up. The fountains—and all other similar initiatives Hamilton has tried since—are all exercises in branding. They deny central issues of identity, instead asserting varied claims of legitimacy.

*****

Finally, I want to say that as a Pakeha, and visitor to Hamilton, you have challenged me to consider the undercurrents of identity that ultimately define it as a place. I’m not sure how to acknowledge this history, other than to give your words air here, finding a way around your unwillingness to talk in a more official capacity.

The hope was to use our project to speak to these histories, to get beyond the echoes altogether perhaps… but I’m sorry to inform you that after a series of long delays, our project has now been cancelled, due to some sort of lack of confidence on behalf of the governing bodies involved. Evidently, our work was hard to place within their understanding of what public art should be, and more importantly, what it should DO. I think perhaps they just wanted us to liven up the space a bit, as opposed to critically engaging with the locale by challenging notions of identity and belonging? Could it be that our exploring these underlying notions had something to do with the project’s failure? And if that’s the case, maybe the whole debacle wasn’t so much of a failure after all?

Oh, and what became of the fountains? The Fountain City moniker never made it out of the 1980s, but echoes of the project still exist. The Centennial Fountain now sits dry and cobwebbed out the back of Founders Theatre; the water supply having been turned off indefinitely around 2011 amidst talk of droughts and water management.

In The Image of the City, Lynch proposes that we all have a mental image of a place. This image is subjective—it exists as an amalgamation of what we see around us, and our memories/histories/previous experiences; things we project out onto the built urban environment. Taking this idea of the mental image and applying it to Hamilton, I wonder where the fountains sit in the collective memory? Perhaps lurking somewhere in the back of Hamiltonians minds, allowed out of the darkness every now and then when somebody walks into the foyer of Founders Theatre, or through Garden Place, sees a fountain, and thinks ‘oh yeah, that used to be a thing...’