The Ground Swallows You

This essay first appeared in The Ground Swallows You Part 1. The publication was released as part of my solo show of the same name at Blue Oyster Art Project Space in April 2016.

All is a plenum (and thus all matter is connected together) […] And consequently every body feels the effect of all that takes place in the universe, so that he who sees all might read in each what is happening everywhere, and even what has happened or shall happen, observing in the present that which is far off as well in time as in place.1

– G.W. Leibniz via Hito Steyerl

The Path of the Josco

The water that fills Otago Harbour is cloudy—wade into it and your legs disappear beneath you. Often the harbour is so shallow that large sandbanks are exposed through the middle at low tide. A narrow channel skirts the western edge—dredged regularly to allow ships to travel past Port Chalmers and into the city of Dunedin.

In early November 2015 the Josco Suzhou made its way up this channel—though you won’t find evidence of this in official shipping records. Not because of any great conspiracy, but because it was never really here. It didn’t stop at a major port, or stay long enough to become a feature. This is the nature of shipping on the high seas; an open space that enables a vessel flying the flag of Hong Kong to enter New Zealand waters, unload cargo from the Western Saharan port of Laayoune to the Ravensdown fertiliser factory in Dunedin and, with minimal fuss, be on its way again.

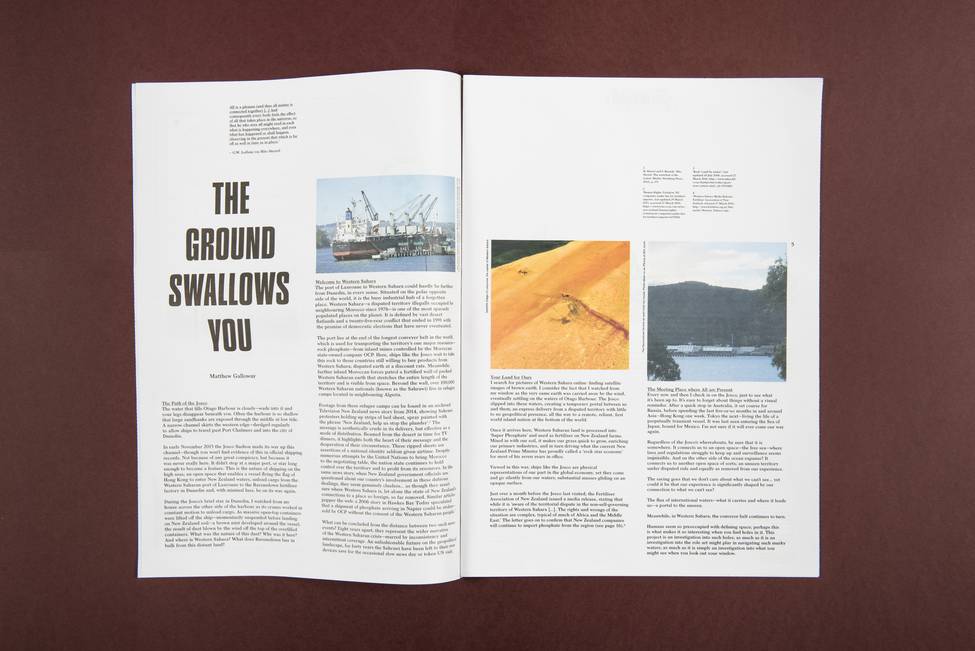

During the Josco’s brief stay in Dunedin, I watched from my house across the other side of the harbour as its cranes worked in constant motion to unload cargo. As massive open-top containers were lifted off the ship—momentarily suspended before landing on New Zealand soil—a brown mist developed around the vessel; the result of dust blown by the wind off the top of the overfilled containers. What was the nature of this dust? Why was it here? And where is Western Sahara? What does Ravensdown buy in bulk from this distant land?

The Josco Suzhou unloading Western Saharan rock phosphate at the Ravensdown factory, Dunedin. Photograph taken by marinetraffic.com user John Wilson on the 2nd of November, 2015

Welcome to Western Sahara

The port of Laayoune in Western Sahara could hardly be further from Dunedin, in every sense. Situated on the polar opposite side of the world, it is the busy industrial hub of a forgotten place. Western Sahara—a disputed territory illegally occupied by neighbouring Morocco since 1976—is one of the most sparsely populated places on the planet. It is defined by vast desert flatlands and a twenty-five-year conflict that ended in 1991 with the promise of democratic elections that have never eventuated.

The port lies at the end of the longest conveyer belt in the world, which is used for transporting the territory’s one major resource—rock phosphate—from inland mines controlled by the Moroccan state-owned company OCP. Here, ships like the Josco wait to take this rock to those countries still willing to buy products from Western Sahara; disputed earth at a discount rate. Meanwhile, further inland Moroccan forces patrol a fortified wall of packed Western Saharan earth that stretches the entire length of the territory and is visible from space. Beyond the wall, over 100,000 Western Saharan nationals (known as the Sahrawi) live in refugee camps located in neighbouring Algeria.

Footage from these refugee camps can be found in an archived Television New Zealand news story from 2014, showing Sahrawi protesters holding up strips of bed sheet, spray painted with the phrase ‘New Zealand, help us stop the plunder’.2 The message is aesthetically crude in its delivery, but effective as a mode of distribution. Beamed from the desert in time for TV dinners, it highlights both the heart of their message and the desperation of their circumstance. These ripped sheets are assertions of a national identity seldom given airtime. Despite numerous attempts by the United Nations to bring Morocco to the negotiating table, the nation state continues to hold control over the territory and to profit from its resources. In the same news story, when New Zealand government officials are questioned about our country’s involvement in these dubious dealings, they seem genuinely clueless… as though they aren’t sure where Western Sahara is, let alone the state of New Zealand’s connections to a place so foreign, so far removed. Similar articles pepper the web: a 2006 story in Hawkes Bay Today speculated that a shipment of phosphate arriving in Napier could be stolen—sold by OCP without the consent of the Western Saharan people.3

What can be concluded from the distance between two such news events? Eight years apart, they represent the wider narrative of the Western Saharan crisis—marred by inconsistency and intermittent coverage. An unfashionable fixture on the geopolitical landscape, for forty years the Sahrawi have been left to their own devices save for the occasional slow news day or token UN visit.

Satellite image of Laayoune, the capital of Western Sahara

Your Land for Ours

I search for pictures of Western Sahara online: finding satellite images of brown earth. I consider the fact that I watched from my window as the very same earth was carried away by the wind, eventually settling on the waters of Otago Harbour. The Josco slipped into these waters, creating a temporary portal between us and them; an express delivery from a disputed territory with little to no geopolitical presence, all the way to a remote, reliant, first world island nation at the bottom of the world.

Once it arrives here, Western Saharan land is processed into ‘Super Phosphate’ and used as fertiliser on New Zealand farms. Mixed in with our soil, it makes our grass quick to grow, enriching our primary industries, and in turn driving what the current New Zealand Prime Minster has proudly called a ‘rock star economy’ for most of his seven years in office.

Viewed in this way, ships like the Josco are physical representations of our part in the global economy, yet they come and go silently from our waters; substantial masses gliding on an opaque surface. Just over a month before the Josco last visited, the Fertiliser Association of New Zealand issued a media release, stating that while it is ‘aware of the territorial dispute in the non-self-governing territory of Western Sahara […]. The rights and wrongs of the situation are complex, typical of much of Africa and the Middle East.’ The letter goes on to confirm that New Zealand companies will continue to import phosphate from the region.4

The Ravensdown factory as seen from my house. Photo taken on an iPhone at 50% zoom

The Meeting Place where All are Present

Every now and then I check in on the Josco, just to see what it’s been up to. It’s easy to forget about things without a visual reminder. After a quick stop in Australia, it set course for Russia, before spending the last five-or-so months in and around Asia—Hong Kong one week, Tokyo the next—living the life of a perpetually transient vessel. It was last seen entering the Sea of Japan, bound for Mexico. I’m not sure if it will ever come our way again.

Regardless of the Josco’s whereabouts, be sure that it is somewhere. It connects us to an open space—the free sea—where laws and regulations struggle to keep up and surveillance seems impossible. And on the other side of the ocean expanse? It connects us to another open space of sorts; an unseen territory under disputed rule and equally as removed from our experience.

The saying goes that we don’t care about what we can’t see… yet could it be that our experience is significantly shaped by our connection to what we can’t see?

The flux of international waters—what it carries and where it leads us—a portal to the unseen. Meanwhile, in Western Sahara, the conveyor belt continues to turn.

Humans seem so preoccupied with defining space; perhaps this is what makes it so interesting when you find holes in it. This project is an investigation into such holes; as much as it is an investigation into the role art might play in navigating such murky waters; as much as it is simply an investigation into what you might see when you look out your window.