Out of the Shadows

This article originally appeared in The Silver Bulletin #8. Though it can be read as a stand alone piece, it does follow on from two previous articles - Art Over Nature Over Art and Ways of Finding and Marking.

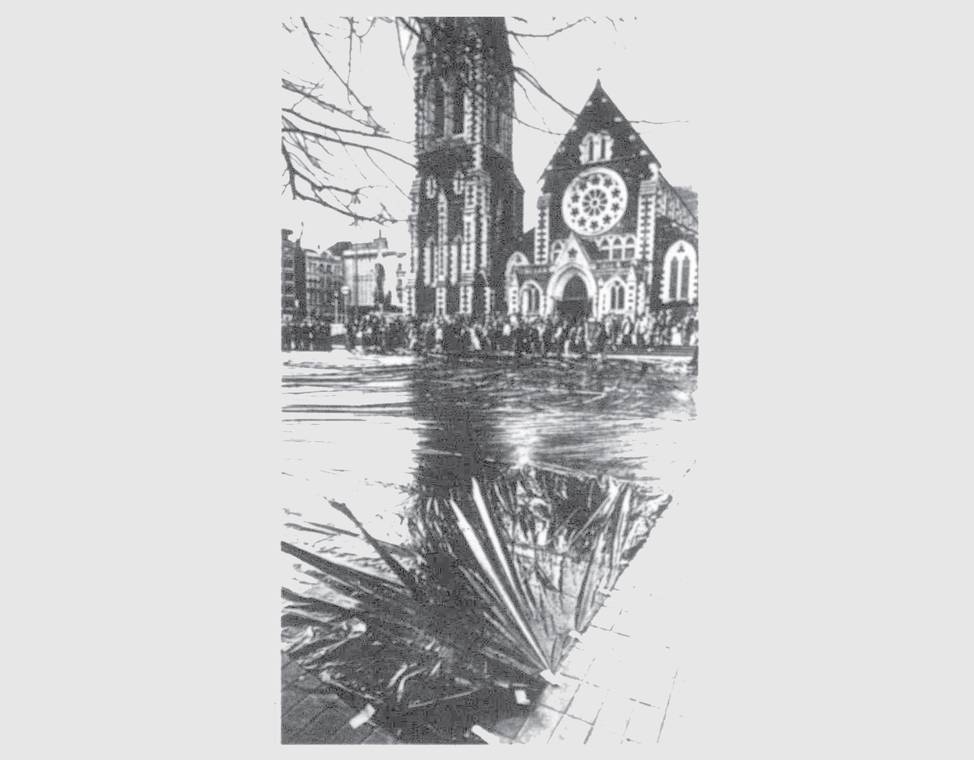

From The Press, July 18, 1987, black polythene lines Cathedral Square.

On the 17th of July 1987, a protest group, known as the Protect Victoria Square Society, spread black polythene on the ground of Cathedral Square to represent a shadow—that of the Victoria Square Tower, a bold, future-facing mega-structure to be built in near-by Victoria Square by the newly formed Tourist Towers Ltd.

Designed by local architects Warren and Mahoney, the 167m circular tower was to include a revolving restaurant and nightclub and promised to be a must-see attraction for tourists; creating 320 jobs, generating $23 million in annual revenue and—according to the protestors—casting a literal and metaphorical shadow over both Cathedral Square and the Christchurch Cathedral, a building symbolically linked to the city’s identity and heritage. In an example of just how controversial this proposal was, the protest’s aesthetically astute and illustrative ‘foreshadowing’ of the Tower’s likely effects on its surrounds highlights the lengths the public were willing to go to in order to have their voice heard on the matter. But what the exercise also unwittingly illustrated was the power of ‘broadcasting architecture’—the success with which a building is able to be translated across different mediums and still be recognisable. The term ‘broadcasting architecture’ describes a sort of iconic currency: the more easily a building, a photograph of the building and a two-dimensional logo of that building are recognisably interchangeable, the higher the iconic value of the structure. So generic was design of the monolithic Victoria Square Tower, that members of the public were able to broadcast its shape onto the ground in black plastic whist only having initial plans and models to go by.

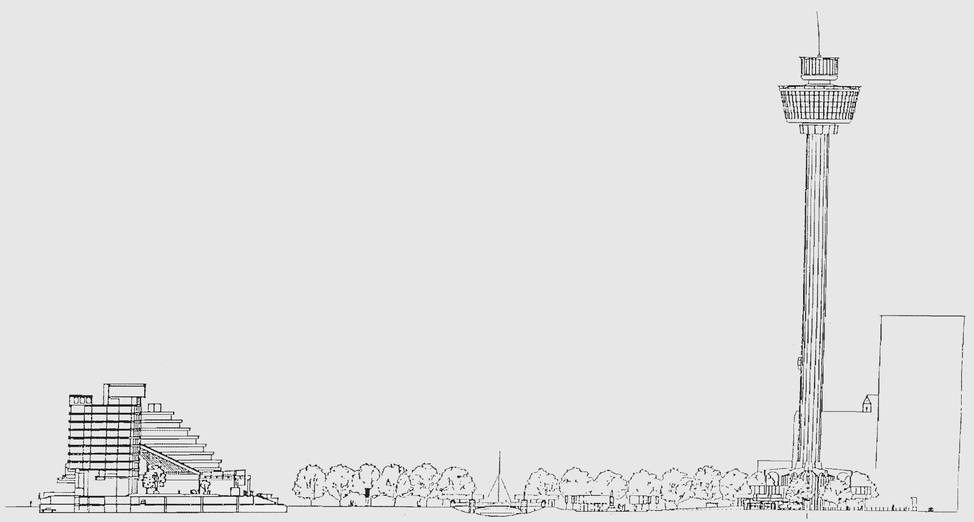

The Tower proposed for Victoria Square in context of the larger redevelopment of the Square, which included the shortening of Victoria Street and making it pedestrian only. The now demolished Crowne Plaza Hotel (also designed by Warren and Mahoney) was built where the road used to run through.

By the 1980s this kind of structure, the ‘Great Tower’, had become synonymous with tourism and promised the kind of iconoclastic sensationalism that could put a city on the world stage. After a foundation of early trailblazers in the 60s and 70s, there was a renewed global rush to be the next city to build a tower; to create an architectural center point for both outsiders and residents and—in many cases—act as a new city logo. The Tower could be broadcast out on official documents, be the first thing seen when flying into the city, be ever-present on the skyline (visible from anywhere within the city or from out-lying suburbs) and be the subject matter of choice when buying a postcard to send to relatives back home. The tower was broadcasting architecture at its most digestible and pragmatic—both visually representing, and actually functioning as, a giant antenna—connecting its city to the outside world by symbolism and satellite. It brought with it a set of well-known troupes, speaking a language that visitors to the city would instantly understand. The tower ideology was one that played off of the importance of an icon to the identity of a place; an icon’s ability to not just connect a symbol with a location, but to help lure in tourists, and then gently suggest what they should be looking at.

Tourist Towers Ltd was propositioning Christchurch residents with a new icon, Christchurch tourists with a distinctive attraction, and offering both a panoramic view of the city from ‘above the smog line’.

The Victoria Square Tower proposed not just to change the city’s skyline, it threatened to completely undermine the carefully constructed Christchurch identity. In the same spirit that gave birth to the 1989 slogan ‘The City That Shines’, the Tower represented an aspirational vision for Christchurch... for what it could be... a vision not shared by everyone. The transformative effect an intervention of such scale could have on its location proved the catalyst for an unprecedented level of controversy and public debate in the city. The Protect Victoria Square Society was formed soon after the first public unveiling of the proposal and within days of their shadow protest (after initially advancing the Tower proposal at every juncture) the City Council seemed to shift its support away from the Tower, distancing itself from the decision making process by employing an independent commission to recommend the final outcome of the proposal. When it was revealed a change in city zoning laws was needed allow the Tower to be built, the waters started to become increasingly murky for Tourist Towers Ltd. By the time the commissioners report was released in April 1988 recommending the council oppose any zoning changes, the dream was over.

A question had been asked of the city, and the response was resounding. An icon of the type the Tower was proposing to be wasn’t needed—it didn’t fit within the pre-existing cultural and architectural fabric of the place. Besides, Christchurch already had its icon: the Christchurch Cathedral, soon to be immortalised as the city logo, albeit a representation somewhat removed from the actual shape of the building.

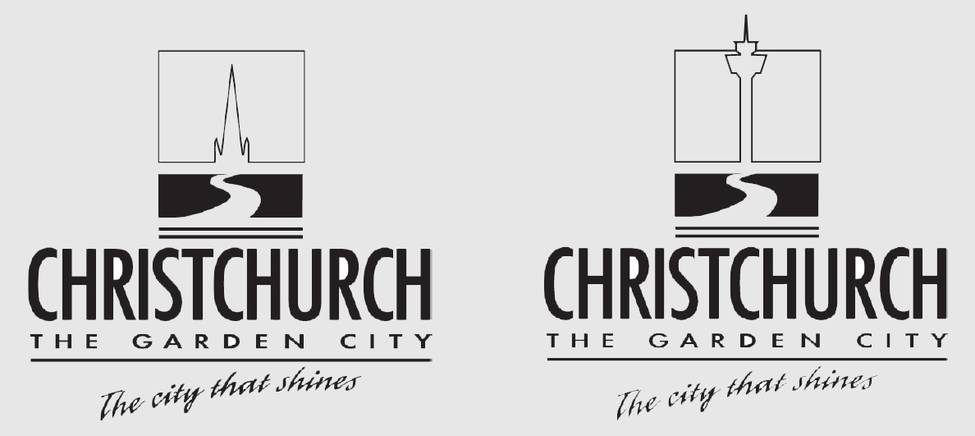

The Christchurch City Council logo of 1989 solidified the Cathedral’s place as city icon. However, had the Tower been built it may well have usurped the Cathedral—leading to something like the speculative logo immediately above.

The Christchurch of the late 1980’s had no room for the Victoria Square Tower.

But what about the Christchurch of 2012 and beyond? With the future of a half-demolished Cathedral shrouded in uncertainty and promises of a new city just around the corner... where will we find our icon?

In a low-rise city, what will stand out?

The answer may lie with the Christchurch City Council logo, which still awkwardly represents something no longer there. What if rather than existing as a memorial to pre-earthquake Christchurch as it currently does, it could instead be viewed as a projection of future possibilities and solutions? Seen as a simple two-dimensional blueprint for a structure, perhaps the logo is a foreshadowing of a new city icon? What if the logo was kept, and a new architectural icon built that, unlike the Cathedral, actually looks like the building represented on the logo? And what if a prototype for this new icon already exists?

WELCOME TO THE RYUGYONG HOTEL

On the other side of the world and situated at the heart of North Korea’s capital city of Pyongyang stands the Ryugyong Hotel—a pyramid-shaped mega-tower so iconic that its image has travelled far outside the veiled seclusion of its location. First conceived of as the crown jewel of Kim Il Sung’s 40 year rebuild of the city after it was effectively razed to the ground during the Korean War, construction on the building began in 1987—moving ahead quickly under Kim’s regime while the people of Christchurch stopped Tourist Towers Ltd. in their tracks. Whether or not those responsible for the stylistic representation of the Christchurch Cathedral on the Christchurch City Council logo were aware of the hotel’s construction or not must be left to speculation... but certainly the visual likeness between the two symbols—one two-dimensional and one three—is uncanny. With the power of architecture as a tool for city branding already well documented, it’s not hard to imagine twin towers—one in Pyongyang and one in Christchurch—as symbolic catalysts for a meeting of two geologically and politically distinct municipalities. Both existing on the periphery (albeit for different reasons) and both having faced massive city rebuilds within the past century. Perhaps the question could be asked; what do these two cities have to offer one another? Is a highly improbably yet possibly fertile relationship worth exploring here? Wikipedia describes Sister City relationships as ‘cooperative agreements between geographically and politically distinct areas to promote cultural and commercial ties’. Could two places be more distinct yet still share such pertinent common ground?