Interview: The National Grid

This interview first appeared in Points of Departure #1. I was interested in talking to Luke and Jonty about The National Grid, and more specifically about how the project is affected or framed by being from New Zealand... the importance of distribution when working from a small country at the bottom of the world.

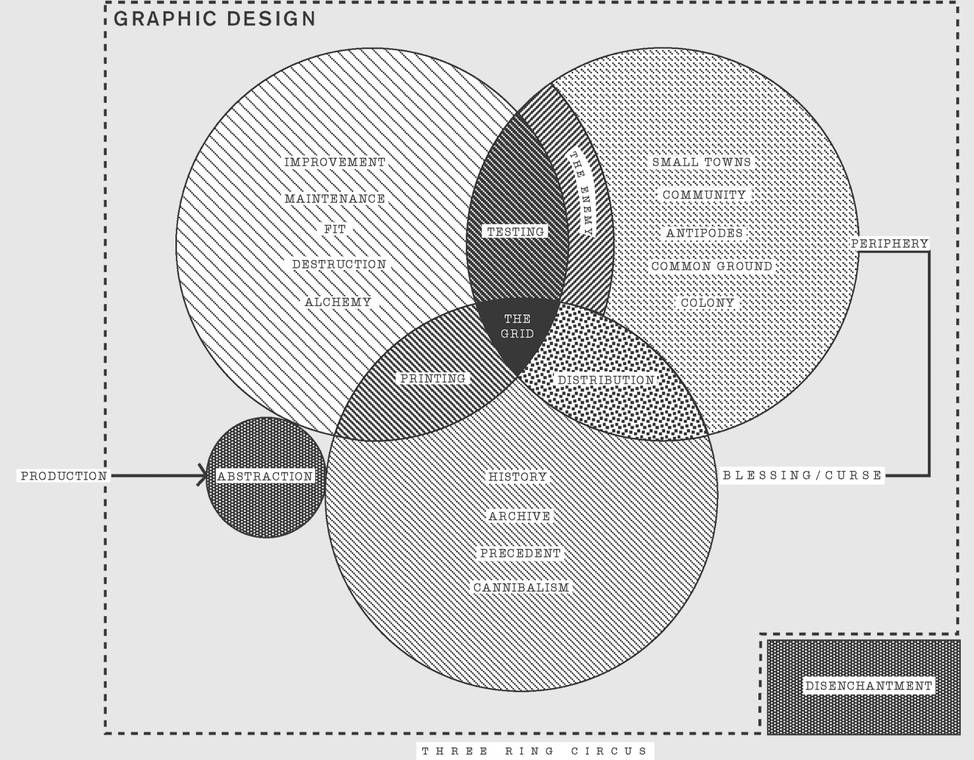

“Not quite ‘magazine’ and not quite ‘academic journal’, The National Grid attempts to chart a path through the murky wasteland between the professional practice of graphic design and its troublesome academic manifestations.”

- Editors Luke Wood & Jonty Valentine

Interview conducted over email between August and November 2011.

Matthew Galloway: I wanted to start at the beginning: The National Grid (TNG) 1 and the most straight up attempt at an editorial in any issue of the publication to date. It definitely feels like a kind of ‘pushing out the boat’ editorial — a number of musings and blanket statements of intentions for TNG and motivating factors for producing it. One theme that comes through is your perceived need for a publication like TNG in New Zealand. I’m wondering — seven issues in — how you feel TNG has been received... and whether you think it has filled these perceived needs/gaps?

Luke Wood: I think we were fairly confident there was a desire amongst a few people here in New Zealand to see and to read something different about graphic design. At the time I don’t think we were probably able to be very articulate about what that was, but I think we were both happy to just get it started and to see what would come out of it. Although when I say “happy” there was always some anxiety about our not being ‘real’ writers. Or editors actually. I think we both felt a bit like we were pretending to start with.

I’ve said often that we initially conceived of the publication as being quite specifically for a New Zealand audience, and even more specifically for graphic designers. That was where we thought there was a hole. Now, five years later, I certainly don’t think it fills this hole. But, I do think it ‘points’ to it at least — by representing contemporary projects and practices that wouldn’t be seen elsewhere, and also through the focus on local historical content.

Our ambitions for the thing have changed a bit since we wrote that first editorial. We do now have a bit of an audience in New Zealand, but we still sell most of the print-run overseas. We thought more graphic designers here would be interested, but most aren’t. I think I, personally, misjudged that. Obviously some are, and those that are into it are very supportive, but it is a niche publication. Those grand ideas we had in issue 1 have been honed down to a much finer point now.

Jonty Valentine: Maybe I’m feeling optimistic because quite a lot of people turned up to the Auckland launch of our last issue (#7) I do think there is an audience here, so perhaps TNG has filled a need or gap. But I think more importantly it has provided a gathering point for a community. I think just to qualify that though:

1. It was mostly students or recent graduates at the launch — which is interesting to the extent that they now take for granted that there should/could be a publication like TNG in New Zealand.

2. I do think that a lot of our peers in the design industry (the establishment) do support us. But I guess we were naïve to think that they would all have a McCahon Types story or a Possibles and Probables story for us that would be rejected by ProDesign.

3. TNG may indeed be seen by many as a fine art publication. Which is interesting only because we have always argued against this. And we have often tried to contradict the growing (but also I think hackneyed) trend of promoting interdisciplinary art practice.

4. We need to acknowledge that design related independent publishing has had a resurgence in the last few years even here in New Zealand — but this is obviously not because of us. Really we were just a bit ahead of people here in following overseas publications like Dot Dot Dot, Oase, Revolver Publishing, Cabinet, Metropolis M, and now too many to name…

5. And while we wanted to define ourselves in opposition to ProDesign, we also wanted to be seen as breaking from (and having a different audience and contributors to) publications like Log Illustrated, Natural Selection, White Fungus, The Pander, and now Hue and Cry... And by breaking from I also mean following.

6. What is most interesting about reading TNG 1 again is in remembering the adolescent feeling that what we were doing was new here. But now of course with hindsight it just seems like we were on some international bandwagon. Which is fine, but it problematises the idea of there being a “need” or a gap a bit. I do still like the idea of there being a need. We did believe that in issue 1, but now I guess it was/is merely a trend. Which is fine too.

Maybe I’m feeling pessimistic because Rick Poynor has given up on Graphic Design History.* Also I got out my old Émigré magazines the other week thinking I should read them all again. And I’m also reminded of recently looking through Max Hailstone’s library of journals that all supposedly filled a need at some time too: Octavo, Typographische Monatsblatter, Baseline, Design Quarterly, The Monotype Reader, The Journal of Typographic Research, Illustration 63, The Penrose Annual…

[But this is not a eulogy]

*Out of the Studio: Graphic Design History and Visual Studies, Rick Poynor, www.designobserver.com

MG: I was interested in reading that Rick Poynor text, in that it caused me to reflect on what history might even mean in a graphic design context. For example, your idea of a history of graphic design will be different to that of a student who turns up to launch parties assuming The National Grid (or something like it) has always been around... but I think also because design has such a fragmented history; one that comes from the lines of printing, advertising, illustration and typography to name a few. I’m just toying with idea that someone like Rick was trying too hard to pin design down, that maybe publications like The National Grid (and its contemporaries/predecessors) are naturally writing a history? I’m thinking here about the publication being dually a venue for discourse and a chronicling of New Zealand design history (Robert Coupland Harding, Joseph Churchward, Max Hailstone etc.) and being an example of current trends in and of itself... Actually just as an extra... is The National Grid still trendy? Has it ever been? I know you talk about people’s initial reactions to it as not looking designed...

JV: Yeah, I guess the issue you are getting at is about the production of histories or the ethics of establishing a history and maybe about creating alternative histories. Because I think it is important to question how histories are written — I mean as opposed to just thinking of them as being really real or true or “natural”. Now I’m sure Noel Waite would have a lot to say about this, but for example, I am really interested in how David Bennewith in a sense “discovered” Joseph Churchward. But of course he was always there and a lot of people knew him, in fact he was very well known to his generation of designers, but somehow his work was lost to the rest of us — because it wasn’t written about. Then David produced his book and Joseph was all over the place. (I guess Luke and Noel covered this in Issue 6).

But today this makes me think of three things:

1. Design for Design’s sake.

At the start we were motivated to uncover a new Design history where there had been very little before. By that we meant to join up the “fragmented history” you refer to and stake a claim for a Graphic Design History as opposed to Art History or Design in general. This was a modernist differentiation of cultural spheres thing. So David’s book is a great example of that — [re]discovering Joseph’s work for us type designers.

2. Diverging, multiple or alternative versions of history.

But we also wrote quite a bit about wanting to write an alternative, peripheral, local history of Graphic Design on our terms. We meant alternative to the Better By Design or ProDesign versions of history that emphasise dumb product design, marketing, innovation myths etc. But also we had some ideas about the tone we wanted to write in — not academic, in our own accents. Again to point at David’s book, what I think was really significant about his book was its poetic means of address, its tone. I think that is what was really alternative/foreign for New Zealand design. But then of course it was published in the Netherlands.

3. Good or Bad history.

I think finally, now that we have matured a bit, the other issue for us — and this might be at odds with the above — is the responsibility of writing really well researched history. I might just be saying this because I was talking to Christopher Thompson the other day, and he made me very insecure about ever pretending to write about design. But he did remind me that there is such a thing as seriously deeply researched, and widely contextualised history and there is equally such a thing as superficial charlatan anecdotal gossip. I guess we are still somewhere in between.

And yes I think TNG is trendy. We will look back at it in ten years and cringe.

LW: My interest in local histories of graphic design came quite specifically from my dissatisfaction with the way things are here, in the so-called ‘industry’, right now. I’m interested in finding people who’ve practiced graphic design in different sorts of ways in the past, and that these examples might provide a plausible alternative for me now. Robert Coupland Harding was interesting in this sense, his journal Typo being an interesting sort of precedent for what we are doing with The National Grid a bit more than one hundred years later. Likewise Bruce Russell’s work with his record labels. In this sense the histories I’m interested in are specific to the projects I’m working on, and I’m quite selfish in that sense. For me there’s no altruistic feeling that I must go out and write a history of New Zealand graphic design. To some extent I do share Jonty’s anxiety about not really being ‘qualified’ to be doing this sort of work, but in another way I feel like what we’re doing is sort of different anyway. This is what I was trying to get at in that interview with Noel Waite. I was pushing this idea that as practitioners of graphic design we engage with primary historical research in a way that is fundamentally different to the trained historian. I was using David’s book as an example of how this approach that I wanted to articulate could work. Through the conversation with Noel I realised I was overly-romanticising this difference I guess, but what comes out is a definite difference in perspective, in terms of what seems important or not. Like simply the fact that it took David to do a book on Joseph Churchward. No historians were looking at him. And if they were then it wasn’t being put anywhere we would have seen it. And there’s something in that too. When I met Noel I quickly realised he was different to other historians in the sense that he saw what he was researching as being directly related to contemporary graphic design. There are a bunch of people who do similar research to Noel, ‘bibliographical historians’, but they don’t see that connection, and they are critically dislocated from graphic design. Their field is printing, and the technical history of that. Which brings me back to Jonty’s “cultural spheres” comment. How you see history depends upon how you cut history up. I think we might cut it up differently to the trained historian? I can’t see Bruce Russell or Dylan Herkes making it into a history of New Zealand graphic design otherwise can you?

This connects to your comment Matt, when you say graphic design has a fragmented history. Let’s remember that graphic design didn’t even really exist until the 1950s. And that universities still don’t know what to do with it. Or where to put it. Should it be in the art school, should it be a social science, should it even be in the university? We often reference Stuart Bailey calling graphic design a ghost, because it illustrates this point so well. It really depends on your perspective. Up until more recently I’ve thought of graphic design simply as an extension of the history of printing and typography, and of writing to some extent. However lately I’ve been thinking of it within the trajectory of painting more specifically. I’m interested in the allowance we give painting, to simply provide visual pleasure. Graphic design is so bound up in conversations about usefulness, but I just want this record cover I’m doing to look good, and to stop people in their tracks and look at it for a second or two.

MG: Ok, I want to pick up on a couple of things that each of you said, and try to tie them together... Jonty — your comment about writing in your own “accents” and thinking of The National Grid as an “Outpost”. Luke — your comment about graphic design as “a ghost” and the allowance for painting to be measured on purely aesthetic principles. Getting back to the first issue editorial, Luke, you are on about similar themes of thinking about design less in terms of usefulness/problem-solving and more in terms of resonance. We started this interview off by talking about a distinct “need” for The National Grid, and certainly, talking about writing alternate histories etc., there is a purpose or usefulness to the publication that we can define. But I wanted to ask if you felt TNG existed as an example of ‘resonant’ design? Also when I think about resonance I can’t help but think about distribution — the Outpost idea — the publication’s position as being from New Zealand always seemed important... And I don’t think it’s exclusively because New Zealand needed it... there is that nice feeling of being on the wrong side of the world, that you are sending it out to interested parties overseas, and maybe the fact it is coming from the other side of the world is what makes it interesting? Different accents and all...

LW: Resonance refers to the ability of a system to oscillate (more or less) at certain frequencies. Audio feedback is a result of resonance. When I stand in front of my amplifier with my guitar turned up enough, certain frequencies will resonate — the guitar and the amplifier are essentially feeding off each other. Whereas usually the amplifier just feeds off of the guitars input. This feedback loop is interesting in terms of how publications might work. Commercially viable magazines have very large print runs and work through established professional distribution companies. They are paid for, mostly, through advertising. The actual cover price that someone pays for an issue in the shop is a drop in the ocean compared to what the advertisers are pumping into the thing. These magazines get sent out in their tens-of-thousands, people buy them and read them, and maybe they get the next issue and so on. It’s a one-way thing mostly. I had this possibly romantic notion that TNG would operate differently, that if we could get the ‘frequency’ right we could create this self-perpetuating sort of thing — a feedback loop where distributors and readers also become contributors and vice versa. Does that make sense? This fits with that ‘outpost’ thing, which comes from our feeling geographically, but also professionally and academically, isolated. I’ve talked about this before, how TNG has worked as a vehicle of sorts through which Jonty and I have been able to engage with a much wider community of practice than what is necessarily geographically available to us. I like to think of it as a message in a bottle. This is not a new idea; small independent record labels have worked like this for a long time. I always look to rock and roll for direction!

So now when you ask is it an example of resonant design, I’m thinking have we got the thing feeding back and creating a real racket? Well not quite actually, but sort of. I mean it’s not exactly a racket, but more of a low hum. Your question is to do with the aesthetics of the publication though I think? And I guess I’m thinking that any resonance is generated more by the content than the form. But I could be wrong; I don’t really know to be honest. I’ve found that generally people seem to respond in terms of content and not so much in terms of the design. Which is perhaps interesting in itself, being that it is a design publication and what it looks like must surely be at least half of the point? It’s not that we don’t consider it formally. Each issue is approached quite differently in this respect, and I think sometimes we pull of something interesting and sometimes maybe we don’t. To have the freedom to be able to not always pull it off, that’s useful too. But then no one ever talks to us about that? Jonty?

JV: I like Luke’s description of resonance above. Although, I’m not at all musical, so when I think of resonance it is more about how something elicits memories. I don’t think I just mean that in a sentimental way though. More about intertextual echoes, maybe. Is reverberating the same as resonating? Anyway, I think that this still makes sense next to Luke… So, I’m reminded of how we often notice that texts inadvertently resonate within or between issues. I think that is what Luke is getting at with us creating a self-perpetuating “feedback loop” of contributors. Mostly though, I like to think that what could make TNG resonate (and I guess now I mean it in the sense of having a kind of unanticipated combined effect) is when/if it was able to interfere with or contribute to international graphic design discourses. Though I don’t believe that is happening except in a very quiet way. Which is fine, because it’s not like we are aiming to do anything big and ‘worthy’. I’m just hesitating because I’m not sure what we are really ‘feeding back’. I wonder if we are just echoing rather than adding anything new? Maybe that is enough. In a delayed distorted accent and all…

But I can’t help but think it is very quiet (which is not very rock ’n’ roll Luke?).

So how about this then: We are repeating something from over there but sending it back in a slightly distorted way that works a bit like those whispering walls — you know like in St Paul’s or the basement of Grand Central Station (Paul Elliman wrote about this in Forms of Inquiry). If you are in the right place you can hear whispering across the other side of the chamber and above the din. Maybe then that is the bit I like the most. You know, because I do like the idea of design being about keeping secrets, excluding people and being specialised — rather than being about broadcasting spam to hoi polloi.

MG: This idea of “having the freedom… to not always pull it off”, I think it loosely relates to what you were saying about painting — that old definition of an art practice being to make something and make it again and then make it again... this is what leads to a body of work.

There’s an assumption here that starting a publication means you have something to say; you’re in possession of pre-existing ‘orphan’ content maybe (Possibles and Probables, McCahon Types). But beyond issue 1 it then shifts to being a venue for new things to happen and that leads to what Jonty said about resonating between issues; you start to see themes develop or regular contributors become apparent. At the same time as each issue existing as a stand-alone object. So — taking on that artist way of practicing — it’s as if each issue exists as an experiment as well as an outcome? Also, I’m guessing there are some issues you feel are more successful an experiment than others? How do you measure that? Do you think each ‘experiment’ leads to a further distillation of aims and methodology... or only serves to further muddy the waters...

JV: Nice prompt Matt, though I’m going to have to try to ignore my inclination to question your mixing of artistic and scientific metaphors. I do really like the observation that we are working things out by just doing it — in an artistic body of work kind of way. Because my motivation for writing about something is entirely from wanting to try to clarify my thinking for myself — to try to work out what I want to say. This muddying then distilling of ideas may not equally be successful by the time it needs to go to print. But, I have always thought that my texts in TNG are a kind of dry run for when I might ‘properly’ publish them – although I have no idea where that might be. Damn, I’m doing it too — mixing art and science. Do artists usually do dry runs? Or is each work a dry run for the next? Maybe that’s the difference between the art mode and the scientific, i.e. the imperative to measure if the experiment is a success. I guess artists do continually try to improve what they do…?

Sorry, I’ll try to keep to the point. Yes, I do think some TNG issues are more successful than others. But not so much in terms of their mix of written content. This may be contradictory because I think the writing is a crucial thing to evaluate, but (maybe because I’m not really a writer) I just like the range of content and styles in all of the issues. And the reason that I dislike (let’s say) issue 3 is more because of the way it looks: its print quality, and maybe the cover design. However, I do think that the actual value of TNG is in the bigger experiment, which is still developing: all of the issues together, the spin-off projects and the networks we have set up — the on-going body of work.

Hmm. We’ve both said that before. Is it just a cliché? And Luke, do you think your writing has developed, improved since issue 1?

LW: I was talking to Matt about that the other day actually. About how I thought your writing [Jonty] had really improved because you’ve forced yourself to sit down and write an actual ‘article’ for almost every issue, whereas I’ve done more interviews and as a result I don’t think I’ve developed so much as a writer. I want to try and avoid doing so many interviews in the future. I can’t seem to not do interviews. I think I quite like how a publication can act as an ‘in’ when you want to talk to someone, like it legitimises your making contact with someone out of the blue. I also just sort of like talking to people I’m interested in I guess. I’m sitting here remembering that when I interviewed Dylan Herkes in issue 1 I really didn’t know him at all, and now we’re good friends and play in a band together. And then I interviewed Bruce Russell in issue 2, and Bruce and I are pretty well acquainted now, I’ve been doing quite a bit of work with him this year. Sorry this is a bit of a tangent, but worth pointing out in terms of the project, the publication, and my role etc.

In terms of your questions Matt, you’d think each issue should be an improvement on the previous one, and that they would always be getting better and more confident or something. As Jonty’s already pointed out though, it doesn’t seem to work like that. I was pretty happy with issue 6, but feel we’ve slipped back a bit with issue 7 maybe. Although I think 7 has good content, I think we just pushed the formal/aesthetic side of things a bit more with 6. I don’t know, I liked 7 before it went to print, but now I’m not sure about it. It’s funny though, I often don’t like the ‘new’ issue, but then a couple of years later I’ll feel quite happy with it... I think the details disappear, or seem less important, over time. And like Jonty says, the project is the important thing. I do, over time, tend to think of them as a set and not so much as individual things.

MG: Talking about Bruce Russell, Luke, your interview with him in issue 2 picked up on various correlations between the designer-established publication and the musician-established music label. Primarily, both provide the opportunity for greater creative control, and the ability to develop your trade and to experiment... They also sidestep any sort of quality control. What’s your position on that? Does TNG get criticised for this in the academic world? I guess this is also getting back to what Jonty was talking about earlier with the ‘seriously deeply researched, and widely contextualised history’ versus the “superficial charlatan anecdotal gossip”... and TNG sitting in the middle somewhere. Qualified “superficial charlatan anecdotal gossip” maybe? Also related here, with a similar format to each issue, do you ever feel the publication could become formulaic? I can’t help but look to Dot Dot Dot here, and wonder if their experiments in later issues with different ways of producing the publication was about breaking formulas; 15 was produced on location at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, 19 was made up of PDF’s from another project of theirs — The First/Last Newspaper.

LW: It’s funny you say that about Dot Dot Dot, because I actually think of the earlier issues as being more experimental. All the issues up until 15. When Peter Bilak pulled out, Stuart Bailey took it in a very precise sort of direction. Not that I didn’t like that, but it sort of seemed to inhabit more of a grey area when they were both doing it.

The National Grid receives significant funding from Creative New Zealand, and to some extent that must count as quality control? Although to be honest our experience of getting and not-getting that funding proves that it is essentially a lottery. To be academically relevant we would have to have each article ‘peer reviewed’. That means having a panel of other academics that’d read each article and provide feedback, or potentially veto the text. We’d never really imagined TNG being an academic journal, although if it were it would make our working lives as lecturers a lot easier because it would more obviously score points as a ‘research output’. I think when we started the publication we imagined we’d be talking to designers in professional practice first and foremost. I guess in hindsight it should have been obvious that there would be a largely ‘academic’ slant on the publication simply due to the length of the texts. I always used to argue that it was a myth that graphic designers don’t read, but I know now that as a generalisation there is some truth to that.

In issue 7 Noel Waite makes a direct request for us to consider having an article per issue that is peer reviewed. His argument is that some of our articles are actually, already, very academic, and that they should be given that sort of seal of approval that peer review provides in those circles. It would also make TNG a much more attractive publication for other academics to submit things to. I can see his point and it probably is something we should think about for future issues. It is a real shift in terms of my thinking about what the publication is, but also I think a change at this point could be really useful in terms of our longer-term engagement with the project.

Which maybe gets to your last question there about it becoming formulaic? I do feel, after issue 7, that some big changes might be quite good. Jonty and I sort of talked about this in the weekend. Although that was more to do with distribution, and the possibility of finding a publisher, so that we could be freed up to focus on the content more. I don’t necessarily have a problem with a formula if it’s a good formula, but personally I think it’s easier to engage with a project that is evolving over time.