In the Desert, with Peace

This essay originally appeared in The Ground Swallows You Part II. What follows is an account of my time spent in the Sahrawi RefugeeCamps, Tindouf, Algeria in November 2016. I was there as a participant in the 10th edition of ARTifariti: International Art and Human Rights Meeting, held annually in the camps.

Beginning

I remember waking up in the desert. Everyone else was already up, I was alone, it was nearing midday. I got dressed and stepped out into the hallway connected to my room. At the end of the hallway, there was an open door, half covered by a sheer curtain. The curtain was moving rhythmically, blown outwards by the breeze, then back against the wall. Each time the fabric moved, I caught a glimpse of the desert beyond. I walked to the door and pulled the curtain aside, my eyes burning as they adjusted to daylight. There was nothing to see; rock and sand in all directions, dotted with tents and small mud-brick houses—identical to the one in which I had just awoken.

I had arrived in the camps a few hours earlier under the darkness of pre-dawn, marking the end of a four-day journey in which every hour had been spent in some form of transit. My body felt different, as though at some point up in the sky it had been taken apart and put back together but misaligned. As I spent that first morning with my hosts, listening to them speak in Spanish and Arabic to my fellow guest artists and feeling the effects of my transitionary state, I came to the realisation that—for me—this place could no longer exist in the abstract. We imagine what we cannot see, and we let our imaginings take abstract forms. We think in ideas, in representations. These abstractions dig in, persisting through the concrete of experience; through evidence to the contrary. Our understanding of how the world works is built on these abstractions.

Back home, I had seen ships bringing phosphate rock to the Ravensdown factory on the other side of Otago Harbor and traced the routes of these ships back to the people with whom I was now staying. I had read about Morocco’s illegal invasion of their territory in 1975; how they had been driven from their homes, and forced to live in refugee camps across the border in Algeria. I had researched the Moroccan state-owned company OCP, that mines and exports phosphate rock from this occupied territory, putting it on ships and sending it to New Zealand. I had considered the poetic nature of this exchange; disputed earth, transported to the opposite side of the world, to make our soil more fertile, productive, valuable. And now here I was, sent back in the opposite direction, sitting in the home of a Sahrawi refugee family; drinking their tea, eating meals they had prepared, trying to get a laugh out of their children. In that moment, any remaining sense of poetry or abstraction I still had was broken up and reformed into a new understanding of reality; as if a dark spot in my mental image of the world had just been illuminated. The complexities of trade relationships, UN resolutions and peace talks, usurped by the hospitality of a refugee family; the bigger picture shrunken to an interpersonal exchange. When you’ve only ever understood a situation from one point of view, to step through the curtain is to step into a new reality.

********

The rolling hills of the Saharan desert, as seen from the back door of Puja’s house

There were three of us staying in Puja’s home; LL, PM, and I. The house was at the very back edge of the Boujdour camp—one of five connected settlements that collectively make up the Sahrawi Refugee Camps, on the westernmost tip of Algeria. Behind the house, the desert rose up into rolling hills that seemed to go on forever. The valleys between the hills were filled with refuse; rubbish bags, burnt-out cars, dead goats. Scavenging birds would gather around the rubbish during the hottest parts of the day. Every now and then, they all took to the air to chase each other, swarming over the hilltops. On the first night, Puja took us up to the top of the hill directly behind her house, to show us the view back over the camps, and to the desert beyond. In the distance, the Algerian city of Tindouf was just visible; office buildings, a university and the airport we had flown into.

‘Do you think they actually have a sense of their homeland?’ LL had asked later that evening as we ate the meal that Puja had prepared, ‘or do you think they have just been taught to act like that; say the right things?’

Aware of the makeshift shelter we were sitting in; typical of those that had been home to the Sahrawi for over 40 years, I found it hard to imagine a situation in which the absence of a homeland could do anything but sharpen the knowledge of what a homeland represents. But at the same time her provocation was fair; can a nation-state exist without a land to call home? Can a group of people generate a sense of belonging without belonging anywhere? Can nationhood exist as a learnt routine?

These questions began to run through my mind on repeat as I familiarised myself with the surroundings, acclimatising to the way of life. Running in tangent with this was the realisation that my jet-lag had morphed into something else. At night, I would wake with fits of coughing and fever. My condition continued to worsen, to the point where I visited the camps’ medical centre and a doctor gave me a snap-lock bag of antibiotics. My days became a calculation of what I needed to achieve versus how much I needed to rest; whether the wifi was working at the house, or whether I needed to go to the Art School in order to facetime home. Inevitably, at some point each day I would make the 30-minute walk across the desert to the Art School, where everyone would gather for talks and presentations. As I navigated my way through the camp, finding landmarks for my daily journey, I was struck by its placeless quality. It was as if the settlement’s most defining feature was that it didn’t exist. I would think back to the view of a working city in the distance; and the defining features that enable us to make sense of a place. The camps had very few such features. It’s a weird feeling, walking around a place with that kind of quality. LL’s question about nationhood resurfaced; could it be that we are all living out our national identities as a learnt routine? Maybe the only difference is that some routines are more established than others, more built up, decorated.

Weeks later, I read Jacob Mundy’s concept that the Western Saharan conflict fundamentally exists in the imaginary; ‘not imaginary in the sense that it is fiction,’ he wrote: ‘but in the sense that it is largely based on ideas. In the material world, both sides

agree that the dispute is over a piece of land. Yet abstractly, at the level of the “metaconflict,” the dispute stems from mutually exclusive differences in the self-perceptions that ground Moroccan and Western Saharan nationalism.’ 1

As I spent time in the camps, I became aware of another kind of map one could draw in order to understand the Sahrawi place in the world; a map that relies on identity and symbolism as opposed to geography and borders. This map represents the guiding ideas that allow the camps to exist; the reason the Sahrawi remain where they are, hovering just over the border from a land they claim is rightfully theirs. This symbolic, imaginary notion of nationhood and identity keeps them in a state of flux—of un-establishment—because this flux is more definitive than any physical state they can occupy. In the material world, the camps are defined by mud-brick houses prone to melting in the rain, in the imaginary, their material reality acts as a fortification for national identity; a sense of what they have, shaped by what they do not.

Middle

“Peace” is nothing more than a change in the form of conflict.2

– Max Weber

Over the next few days, it became clear that the pills were having no real effect. I returned to the medical centre, where I was told nothing further could be prescribed—there was only one type of antibiotic available in the camps. My condition continued to worsen; I slept for long periods in the afternoon, often waking to find Puja hovering over me, checking my temperature or bringing me a new bottle of water.

In the middle weekend of our stay, it was planned that all artists would travel into the free territory of Western Sahara. The idea was to stay a night or two in Tifariti; a small settlement that acted as a military outpost, with a disused hospital amongst a few other fortifications. As the departure date neared, PM and LL became increasingly concerned about my health given the demands of the trip; travelling 300km into the desert; away from the small shred of civilisation we had in the camps. I was torn between the idea of missing the experience, and the knowledge that I was in no position to go. ‘Matthew, you cannot go on this trip,’ PM finally told me the night before we were due to leave, ‘things could become very bad for you out there.’ I knew he was right. I woke up early the next morning to the sound of my friends leaving, I said goodbye, and then tried to get some more sleep.

With everyone gone, days in the camp passed slowly. I rested, and watched the comings and goings of the household. Puja would wake early, preparing food for the day, baking bread, the children tagging along. This practice of everyday life in the camps felt like a practice of patience and survival. Life was progressing in spite of the situation they found themselves in.

I started to think about the notion of peace. Mainly because I couldn’t shake the idea that peace had abandoned me. I had placed myself inside a reality that was so foreign, and yet could not be ignored. Every day, I would receive messages from home, pictures of my children playing in the ocean, and I would struggle to reconcile what I saw on the screen of my phone with the world around me. I had always understood peace as this attainable goal–an aspirational reality for us all to work towards—a state of being that was possible. I thought I lived in peace. But as I walked through the camps, the rocks crunching under my feet, I thought about what had brought me to this place. Essentially, I was here because I had observed a connection between New Zealand and Western Sahara. In my work, I had used these two places as paradoxes, and put forward the hypothesis that if these two disparate locations can be connected in some way, then surely it follows that everything is connected.

If everything is connected… then can one place have peace, when another does not? As I walked, holes began to appear in my understanding of peace. These holes were characterized by my vision of peace as a reality, as something to be grasped—something to hold. These holes allowed me to see that my conception of peace was hollow. I began to understand peace as purely representational, as a symbol. This shift in my perception enabled me to start to consider its true structure.

Peace; being aspirational—serving some place within a vision of utopia—exists as a tool for identity-making. Its currency lies within an imagined reality, as opposed to an actual state of being. I realised that the material model of peace was the model I had brought into my entire life. I had always had this vague notion that peace existed in pockets, and that these pockets were trying to spread, that certain people were lucky to live in these pockets. But everything about being in the desert taught me otherwise. There is no peace, only peace-as-brand. Only advantage and disadvantage; positions within a fabricated understanding of reality. My existence had always been lived within this fabrication, while the camps represented an entirely different existence, one where peace did not form part of the identity of the place and its people, and yet where—in its absence—peace felt more palpable than anywhere.

********

The view from Puja’s house; looking over the camp and towards the sand storm forming over Tindouf

On the day before the artists were due to return, it started to rain. First came the wind; lifting the dense sand of the desert up into the air, surrounding everyone and everything, masking all visibility and sense of place. Puja came to find me, holding out her cell phone, gesturing for me to listen. I answered the phone, it was her brother who was in Algeria attending university, studying English. ‘Hello, Matthew’, the voice was cracking up down the line; ‘I have been asked to tell you that the rains are coming. You must get a small bag together with your passport and other valuable belongings and sleep in the tent tonight, it is too dangerous in the house.’ I thanked the voice, and hung up. That night, we gathered in the tent together; fortifying the edges from leaks, listening to the rain belting down on the fabric roof. It hardly ever rains in the desert. A year earlier, a massive downpour had destroyed many houses within the camps; roofs had collapsed on top of eroded mud-bricks. Puja made no attempt to hide her anxiety. We drank cup after cup of sweet tea, and finally fell asleep, unsure what would greet us in the morning.

At some point that night, the rain stopped, never settling in to do real damage. The mood amongst the Sahrawi was buoyant, they had escaped the worst. The next day, we were visited by a local translator who had come to let me know that dormant rivers had been flooded throughout the free territories, making it impossible for the convoy to make it back from Tifariti. Each subsequent day, the story would remain the same. There was no way to make contact with them, all I had was the knowledge that rivers continued to run, and as long as that was the case, there was no way back.

Resigned to not knowing, my days fell back into a slow pattern. As I watched my host family live their lives, it was slowly revealed that they were surrounded by extended family; the house next door belonged to Elbarra, Puja’s mother. Cousins, sisters, and grandparents lived across the valley. Most nights would consist of moving from one house to another, drinking tea, talking about current events. The children would fall asleep on the ground next to their elders, Elbarra would move around the room, putting blankets over her grandchildren, comforting them if they woke. At 50 years old, she had lived through each stage of the Morrocan conflict; fleeing her home in Western Sahara as a child, spending her formative years at war, when the camps acted as operative bases. She had raised her children in ceasefire, working to give them an education.

Towards the end of my stay, I recorded an interview with Elbarra. As I listened to her I found no evidence of peace, but strength born in its absence. After the interview I turned off the recording device, and thanked her for her words. She took a moment, looking down at her hands. When she looked up again, I saw that she was crying. Through her tears, she told me how hard she had found it seeing me so sick, lamenting that the language barrier had made it hard for her to help me, to fully express her concern. This display of empathy was hard for me to take, given the story she had just shared.

Finally, the day before we were due to leave, PM, LL and the others returned. A two-night excursion had turned into seven days in the desert with limited food supplies. They had made it back through the mud, taking 30 hours to travel 300km.

End

I left the camps on November 12 at 1am, back through the checkpoints, past the empty artillery shells-turned-road cones. Flying across Algeria, from Tindouf to Algiers, and then across the Mediterranean to Madrid. With 48 hours till my flight home, I checked into a hotel near the airport. Once in my room, I put my bags down and turned on the shower. As I waited for the water to heat up, I caught my image in the bathroom mirror, the first time I’d seen myself in two weeks. The body I saw was unrecognisable to me–thin and weak. I remember finding this image of myself quite shocking… not really the weight loss, but more the degree of transformation one can go through in such a short time. I had been so focused on getting through the experience that I hadn’t really noticed the change. As I dressed, I realised how much my clothes were hanging off of me. This was not the same body I had left home with, these clothes felt like someone else’s.

I slept well that night, and woke up feeling more normal than I had in a while. I had made arrangements with PM to meet in the city and maybe visit some galleries. We met outside the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, it was good to see a familiar face. We spent the morning in the gallery, PM pointing out the works of his local heroes, and contextualising them within the socio-political climate of Spain at the time of their creation. Close to midday—having seen most of the exhibitions—we decided to go find some lunch. Making our way out of gallery, PM suddenly stopped; ‘You’ll want to see Guernica before we leave?’ he asked. Without waiting for an answer, he took a sharp left turn, into a large room near the entrance. In direct contrast to the rest of the gallery, we were suddenly surrounded by a crowd, all positioning for a better view. Through a large partition—out of our immediate line of sight—was a second space, dedicated to one painting; Picasso’s Guernica. Several classes of school children were jostling near the front of the room, on a guided tour with gallery staff. As they cleared out, creating a vacuum, suddenly we were in front of the work, surrounded by the normal gallery quiet. It was a painting I had seen before – the kind that lives in the general consciousness. As always, experiencing a work in the flesh brings new meaning and a heightened understanding. But even still, this experience felt different. Painted by Picasso in 1937, the work depicts the bombing of the Spanish village of Guernica by Nazi and Italian forces at the request of Spanish Nationalists. In a small house, a weeping woman holds a dead child; her face frozen in a distorted horror. Another woman beholds the scene, shedding light from the candle she is holding, while on the ground, several bodies lie dead. In the background, a building is on fire, with another figure hanging out the window. Throughout the painting—which stretches the length of the large gallery space—animals are dispersed amongst the humans, I read the wall text; about the symbolism of the bull, and the wounded horse; representations of nationalism. I looked back at the face of the woman, and I thought of Elbarra. This was her experience too. Only two days earlier, she had shared her story with me, her sister sitting close by for support as she spoke of Spanish colonialism and Moroccan invasion.

We left the gallery to find some lunch, and then said goodbye. PM hugged me and told me to get better. With a few hours before I needed to catch the train to the airport, I wandered the streets of Madrid, somewhat aimlessly, a little exhausted. Nothing was open; as typical on a Sunday.

********

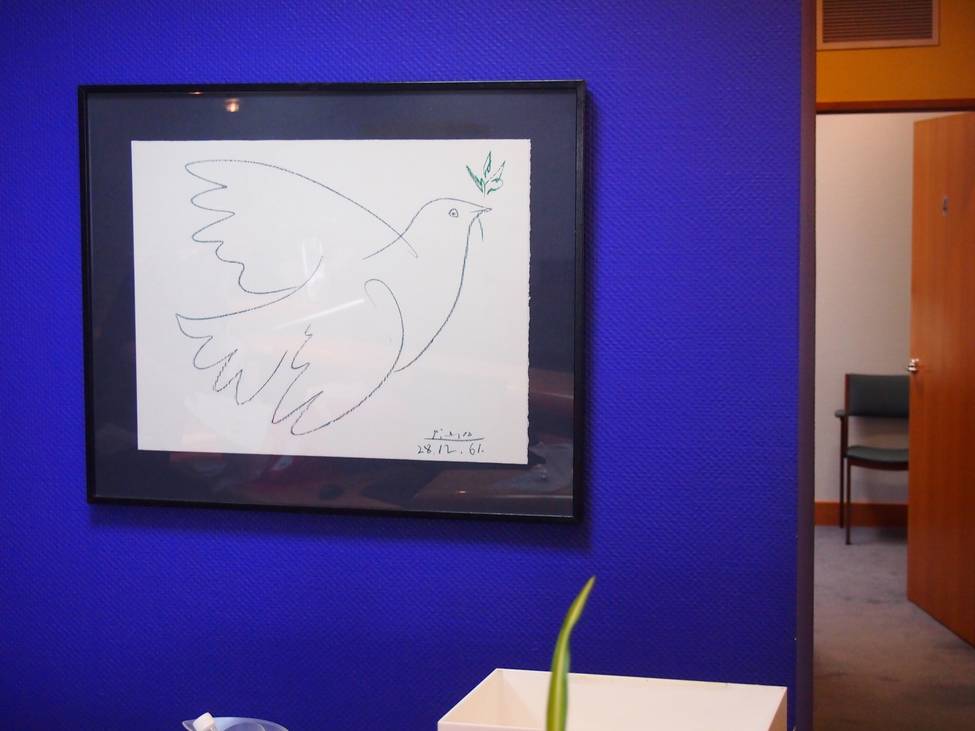

Picasso’s Dove of Peace (28.12.61) In the waiting room of Southern Laboritories, Dunedin

The trip home is a blur, sleeping through fevers, watching movies. When my plane finally landed in Dunedin, I remember thinking how green everything was. My condition seemed worse; pronounced by the long-haul flight perhaps, and by the concern of my family. Pneumonia, my GP said. I got chest x-rays, then blood tests. While the nurse took blood from my arm, we talked about the weather, speculating as to when it would start to feel like summer. I walked back out to the laboratory waiting room, and noticed Picasso’s Dove of Peace, framed behind glass on a blue wall. The bird is drawn in pencil, scribbled almost, in no more than 4 or 5 strokes. The nurse saw me staring at it, and said, ‘we always think it looks so easy to draw, but I don’t think it is.’ The drawing is quick, reproducible. I thought about the meditative quality of the repeated image, the symbolic gesture. I thought of Guernica and Elbarra. I don’t know why Picasso returned to this motif over and over again in the later stages of his life. Perhaps he was trying to will the symbol into existence? Maybe he was trying to draw it until he believed it?

The summer came, I rested, recovered. In February, a new ship docked at Ravensdown. The Mykali had left Western Sahara in November, only a few weeks after me. I biked around the harbour to the factory and watched the massive trays shifting the earth from vessel to shore. The cranes moved slowly and methodically. This desert earth was making the jump, entering a new reality where its troubled past would go unnoticed. Transformed into something more fertile, somewhere more peaceful.

********

In the desert, peace does not exist, the same as everywhere

It is on the tip of every tongue, in the shadow of every moment

But it is only a shadow, with no physical partner

It is a fabrication, a myth

A story, made up to keep the peace.