Black Union

This article originally appeared in the Otago Daily Times on the 30th of May, 2015. At the time of writing, New Zealand was engaged in a two-part referendum process, deciding whether or not to change our National Flag.

“Colonization is not just an early morning fog that dissipates mid-morning as the bright sun of national identity comes out.”1

Between 1979 and 1983 Ralph Hotere produced a large number of studies and paintings that took the Union Jack, drained it of it's colour, and squared it up—in doing so referencing the much-celebrated logo of the 1974 Commonwealth Games in Christchurch. Underneath this motif he stenciled in matter-of-fact capitals: THIS IS A BLACK UNION JACK. Or as a friend of mine read it aloud to me while we stood in front of a smaller work from the series: 'This is a Black Union, Jack'. Both readings make sense, and I think both were intended. The first works as a pragmatic formal observation, but also speaks to the idea of the changing nature of how we saw ourselves as a country at the time—not as the colony we were, but still struggling with the notion of a national identity. Here was a black Union Jack—the shape reminiscent of where we were coming from, but leached of it's colour and in the process now representing our own national colours. It could also be seen as a strikingly simple statement of ownership—alluding to Maori union with the land, and the ongoing debate around race relations in this country. Which brings us to the second reading; this was a message. Specifically, a message aimed at the NZRFU, it's All Blacks, and a government who insisted on playing Rugby with apartheid-era South Africa. Hotere's Black Union series was a collection of protest paintings that playfully juxtaposed the visual harmony of the Union Jack symbol against the disharmony of the political environment he found himself in as a New Zealander. Hotere was using that exact moment in time—one of the most tumultuous in our young history as a nation—to position the Springbok tour within a larger picture of the residual racism and Empirical hangover that continued to have sway over how we saw ourselves as a country, and how that view of who we were in turn feed individual actions and collective attitudes.

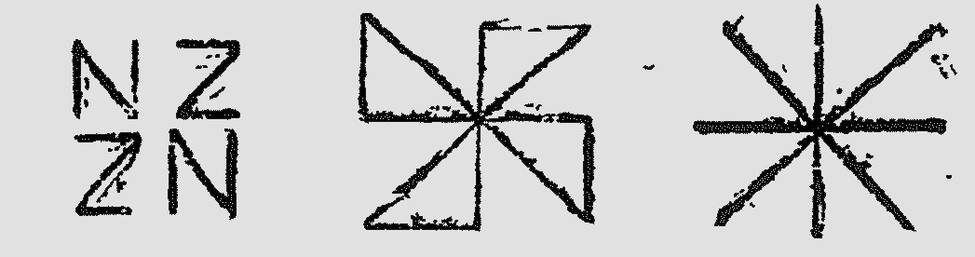

Additionally, it's interesting to view this work as a kind of continuity of the 1974 Games logo, also connected to a sporting event, and also a symbol that could be read as a subversion of the Union Jack. The logo is a good example of modernist logo design, squashing the Union Jack into a square format, and in the process exposing the letters N and Z hiding within the pattern. In a small way, this creates a removal from our British colonial roots (in a logo for a Commonwealth event nonetheless). The colonial brand is overtaken by a sort of national monogram—a morphing and subverting of brand that makes it more ours than theirs.

'74 Commonwealth Games Logo designer Colin Simon wasn't the first to come across this NZ imbedded within the Union Jack—in a letter to the Otago Witness in 1901 entitled 'A Flag For New Zealand', a local resident pointed out the same potential in three simple drawings, the first showing that a capital Z was basically a capital N on it's side, and that the forms could be flipped and were essentially interchangeable. With the second and third drawings the writer then demonstrated how this NZ monogram could be morphed to resemble the basic form of the Union Jack.

On the surface, all three examples here are nothing more than nice visual exercises; formal experiments with line and shape. But, as is most obvious in Hotere's work, this visual evolution also represents our slow departure from a colony of the United Kingdom and towards our own national identity. On this deeper level, looking into these examples of a morphed, altered Union Jack has prompted me to think about the messiness of history; yes the Union Jack can be dismissed as a colonial brand stamped on any number of Commonwealth nations as a sign of Empirical rule… but does that mean it's somehow irrelevant or easily erased from our history? What these examples of a subverted symbol demonstrate is the way the Union Jack—and all that it implies—has informed the images, ideas and values (both good and bad) that continue to shape any notion of identity we now have. It's easy to see it as a symbol from a by-gone era, but symbols accumulate meaning over time; does it simply stand as a relic from our colonial past, keeping us in a holding pattern and casting an empirical shadow? Or is it part of the fabric of who we are, not so easily shaken off despite it's messy history? The hope is that this two-part referendum on the New Zealand flag might inspire such conversations. The current reality seems to be a narrative driven by a Prime Minister more concerned with getting mistaken for an Australian than any other issue the process might have opened the door for.