As Time Goes By

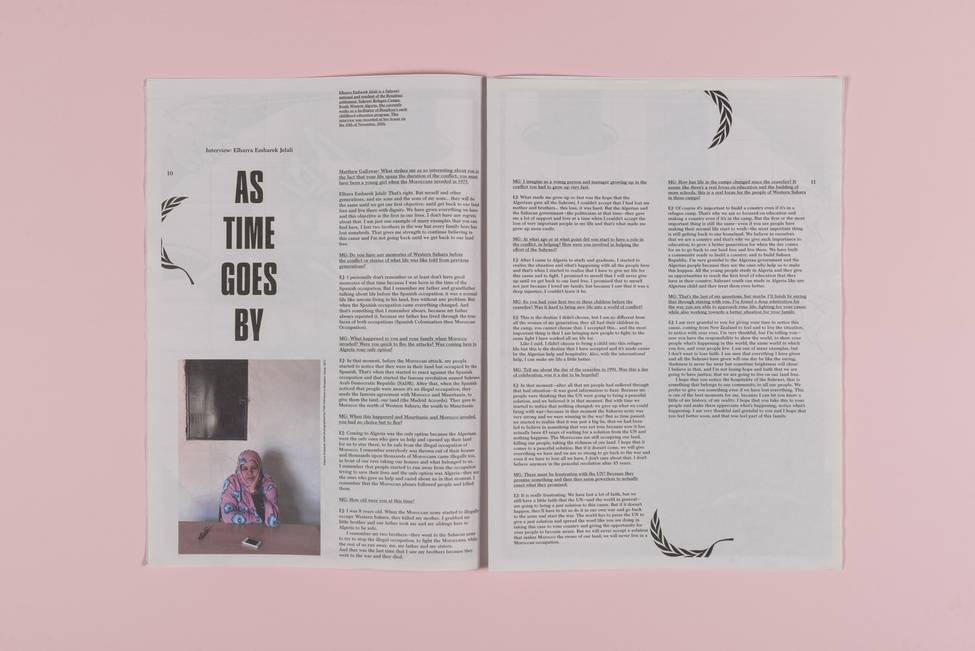

Elbarra Embarek Jelali is a Sahrawi national and resident of the Boujdour settlement, Sahrawi Refugee Camps, South Western Algeria. She currently works as a facilitator of Boujdour’s early childhood education program. This interview was recorded at her house on the 10th of November, 2016.

Matthew Galloway: What strikes me as so interesting about you is the fact that your life spans the duration of the conflict; you must have been a young girl when the Moroccans invaded in 1975.

Elbara Embarek Jelali: That’s right. But myself and other generations, and my sons and the sons of my sons… they will do the same until we get our first objective; until get back to our land free and live there with dignity. We have given everything we have and this objective is the first in our lives. I don’t have any regrets about that. I am just one example of many examples that you can find here, I lost two brothers in the war but every family here has lost somebody. That gives me strength to continue believing in this cause and I’m not going back until we get back to our land free.

MG: Do you have any memories of Western Sahara before the conflict or stories of what life was like told from previous generations?

EJ: I personally don’t remember or at least don’t have good memories of that time because I was born in the time of the Spanish occupation. But I remember my father and grandfather talking about life before the Spanish occupation; it was a normal life like anyone living in his land, free without any problem. But when the Spanish occupation came everything changed. And that’s something that I remember always, because my father always repeated it, because my father has lived through the true faces of both occupations (Spanish Colonisation then Moroccan Occupation).

MG: What happened to you and your family when Morocco invaded? Were you quick to flee the attacks? Was coming here to Algeria your only option?

EJ: In that moment, before the Moroccan attack, my people started to notice that they were in their land but occupied by the Spanish. That’s when they started to react against the Spanish occupation and that started the famous revolution named Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). After that, when the Spanish noticed that people were aware it’s an illegal occupation, they made the famous agreement with Morocco and Mauritania, to give them the land, our land (the Madrid Accords). They gave to Morocco the north of Western Sahara; the south to Mauritania.

MG: When this happened and Mauritania and Morocco invaded, you had no choice but to flee?

EJ: Coming to Algeria was the only option because the Algerians were the only ones who gave us help and opened up their land for us to stay there, to be safe from the illegal occupation of Morocco. I remember everybody was thrown out of their houses and thousands upon thousands of Moroccans came illegally too, in front of our eyes taking our houses and what belonged to us. I remember that people started to run away from the occupation trying to save their lives and the only option was Algeria—they are the ones who gave us help and cared about us in that moment. I remember that the Moroccan planes followed people and killed them.

MG: How old were you at this time?

EJ: I was 8 years old. When the Moroccan army started to illegally occupy Western Sahara, they killed my mother. I grabbed my little brother and our father took me and my siblings here to Algeria to be safe. I remember my two brothers—they went to the Saharan army to try to stop the illegal occupation, to fight the Moroccans, while the rest of us ran away; me, my father and my sisters. And that was the last time that I saw my brothers because they went to the war and they died.

MG: I imagine as a young person and teenager growing up in the conflict you had to grow up very fast.

EJ: What made me grow up so fast was the hope that the Algerians gave all the Sahrawi. I couldn’t accept that I had lost my mother and brothers… this loss, it was hard. But the Algerian and the Saharan government—the politicians at that time—they gave me a lot of support and love at a time when I couldn’t accept the loss of very important people in my life and that’s what made me grow up more easily.

MG: At what age or at what point did you start to have a role in the conflict, in helping? How were you involved in helping the effort of the Sahrawi?

EJ: After I came to Algeria to study and graduate, I started to realise the situation and what’s happening with all the people here and that’s when I started to realise that I have to give my life for this cause and to fight. I promised to myself that I will never give up until we get back to our land free. I promised that to myself not just because I loved my family, but because I saw that it was a deep injustice; I couldn’t leave it be.

MG: So you had your first two or three children before the ceasefire? Was it hard to bring new life into a world of conflict?

EJ: This is the destiny I didn’t choose, but I am no different from all the women of my generation; they all had their children in the camp, you cannot choose that. I accepted this… and the most important thing is that I am bringing new people to fight; to the same fight I have worked all my life for. Like I said, I didn’t choose to bring a child into this refugee life but this is the destiny that I have accepted and it’s made easier by the Algerian help and hospitality. Also, with the international help, I can make my life a little better.

MG: Tell me about the day of the ceasefire in 1991. Was this a day of celebration, was it a day to be hopeful?

EJ: In that moment—after all that my people had suffered through that bad situation—it was good information to hear. Because my people were thinking that the UN were going to bring a peaceful solution, and we believed it in that moment. But with time we started to notice that nothing changed; we gave up what we could bring with war—because in that moment the Saharan army was very strong and we were winning in the war! But as time passed, we started to realise that it was just a big lie, that we had been led to believe in something that was not true because now it has actually been 43 years of waiting for a solution from the UN and nothing happens. The Moroccans are still occupying our land, killing our people, taking the richness of our land. I hope that it comes to a peaceful solution. But if it doesn’t come, we will give everything we have and we are so strong to go back to the war and even if we have to lose all we have, I don’t care about that. I don’t believe anymore in the peaceful resolution after 43 years.

MG: There must be frustration with the UN? Because they promise something and then they seem powerless to actually enact what they promised.

EJ: It is really frustrating. We have lost a lot of faith, but we still have a little faith that the UN—and the world in general—are going to bring a just solution to this cause. But if it doesn’t happen, they’ll have to let us do it in our own way and go back to the arms and start the war. The world has to press the UN to give a just solution and spread the word like you are doing in taking this case to your country and giving the opportunity for your people to become aware. But we will never accept a solution that makes Morocco the owner of our land; we will never live in a Moroccan occupation.

MG: How has life in the camps changed since the ceasefire? It seems like there’s a real focus on education and the building of more schools, this is a real focus for the people of Western Sahara in these camps?

EJ: Of course it’s important to build a country even if it’s in a refugee camp. That’s why we are so focused on education and making a country even if it’s in the camp. But the first or the most important thing is still the same—even if you see people here making their normal life start to work—the most important thing is still getting back to our homeland. We believe in ourselves that we are a country and that’s why we give such importance to education; to grow a better generation for when the day comes for us to go back to our land free and live there. We have built a community ready to build a country; and to build Sahara Republic. I’m very grateful to the Algerian government and the Algerian people because they are the ones who help us to make this happen. All the young people study in Algeria and they give us opportunities to reach the first level of education that they have in their country; Sahrawi youth can study in Algeria like any Algerian child and they treat them even better.

MG: That’s the last of my questions, but maybe I’ll finish by saying that through staying with you, I’ve found a deep admiration for the way you are able to approach your life; fighting for your cause, while also working towards a better situation for your family.

EJ: I am very grateful to you for giving your time to notice this cause, coming from New Zealand to feel and to live the situation, to notice with your eyes. I’m very thankful, but I’m telling you—now you have the responsibility to show the world, to show your people what’s happening in this world; the same world in which you live, and your people live. I am one of many examples, but I don’t want to lose faith. I am sure that everything I have given and all the Sahrawi have given will one day be like the saying, ‘darkness is never far away but sometime brightness will shine’. I believe in that, and I’m not losing hope and faith that we are going to have justice; that we are going to live on our land free. I hope that you notice the hospitality of the Sahrawi, that is something that belongs to our community, to all our people. We prefer to give you something even if we have lost everything. This is one of the best moments for me, because I can let you know a little of my history, of my reality. I hope that you take this to your people and make them appreciate what’s happening, notice what’s happening. I am very thankful and grateful to you and I hope that you feel better soon, and that you feel part of this family.