A Message and a Messenger

This essay originally appeared in Once in a Lifetime: City-building after Disaster in Christchurch. Once in a Lifetime brings together a range of national and international perspectives on city-building and post-disaster urban recovery. The book is edited by Barnaby Bennett, James Dann, Emma Johnson and Ryan Reynolds, and published by Freerange Press. I also designed the cover of the book. You can buy a copy from onceinalifetime.org.nz

‘Place branding increasingly stands as both a visual practice and a modality of governance. That is what makes it slippery. There is much more to branding than a logo or style. It is a manifestation of power.’1

Design, certainly graphic design, is a messenger. It exists as a façade – a way in. It is the means of communicating a message, rather than the message itself. When done well, the two (the message and its means of delivery) can be hard to separate. They play off each other, and meaning is illuminated in a way only manageable through visual form. Usually this relies on a strong message – content that doesn't need dressing up, that simply needs representation in a way that is visually astute or ‘in keeping’, if you like. But how often does this kind of clarity exist in such a process, especially one that involves the murky world of state branding, or the identity of a city?

The hegemonic nature of stamping a trademark symbol or narrative on a place leads to questions of power: who is controlling the narrative, and to what end? From this follows a further series of interlocking questions around perception of place; can a branding exercise ever really alter how a place is perceived from both inside and outside? Most likely, the success of such a process relies little on how a brand might look, or the story it is trying to tell, but more so on how wide the gap is between the perception of a place via its brand narrative and perception gained from a firsthand, on the ground experience of that place. In any situation where the gap is significant, the role of the message and the messenger start to blur, as the latter attempts to fill gaps in absence of the real thing.

On the surface, the Share an Idea campaign that former Christchurch Mayor Bob Parker launched on the 5 May 2011 was all about messages. A mass forum facilitated by the Christchurch City Council (CCC), it consisted of Post-it notes and comment boards filled with messages from the people of Christchurch concerning what they wanted their new city to be. The campaign was labeled as a success, attracting over 100,000 ideas. But besides a good turn out, what – if anything – did this process actually achieve?

After the earthquakes, with much of the fabric of Christchurch’s inner city destroyed, and every aspect of its future shape up for negotiation, natural disaster had suddenly become the defining feature of Christchurch as a place. I want to suggest that, instead of being viewed as a slick crowd-sourcing campaign, Share an Idea should be seen as a rebranding exercise, a first step towards regaining control of the brand narrative of Christchurch – how it should be perceived as a place to both live and visit. Of central importance here is the visual language of the campaign – a combination of bright colours and pictures of Christchurch residents revolving around a speech bubble motif that both illuminates and extends what could be seen as the true motivations of the campaign: to begin rebuilding a sense of place, and to promote a sense of democratised power.

A sense of place

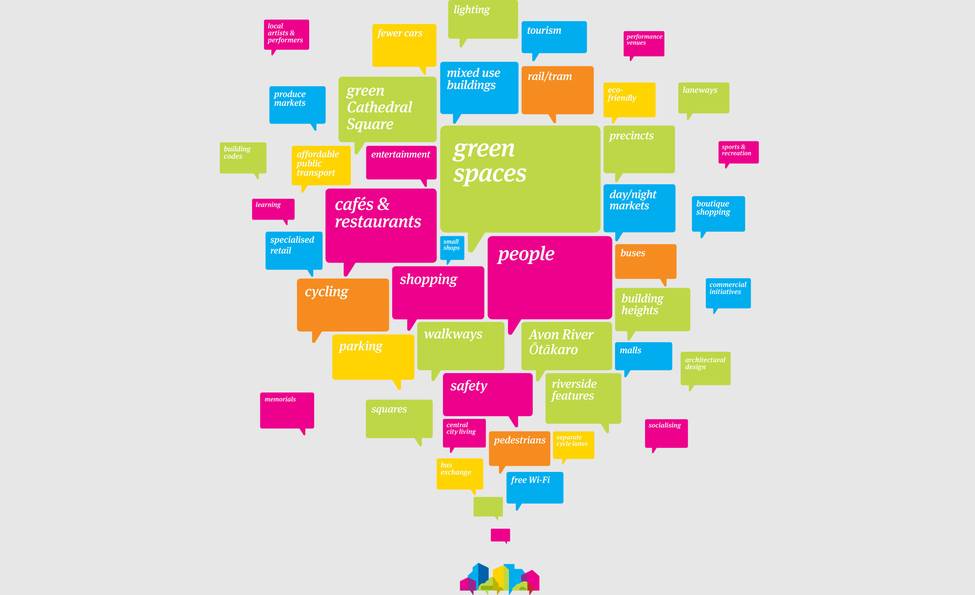

The Share an Idea campaign was sold as a 'creation process'2 – a canvassing of public opinion through a democratic act of participatory design – and presented through an eye-catching visual language of bright, multicoloured speech bubbles (Fig 1). As the campaign developed, these speech bubbles began to fill with messages and suggestions from Christchurch residents – framing them as bright ideas part of a larger conversation that everyone was participating in. These speech bubbles were broadcast in real time through the Share an Idea website and, from there, out through social media platforms and eventually into print media through The Press and a tabloid style citywide mail drop.

Figure 1 - An example of the Share an Idea campaign visuals

But underneath this bright and bubbly exterior, some other incredibly critical ideas were up for grabs – chief among them being the very identity of the city. Before the 22 February 2011 earthquake, Christchurch, known as ‘The Garden City’, had a strong visual identity based around its English heritage buildings and gardens. These elements were brought together on the city logo: the Avon River, surrounded by greenery and sky, leading to the central motif of a stylised Christchurch Cathedral (Fig 2).

Figure 2 - The Christchurch City Council logo remains unchanged in 2014

By May of 2011, with the Cathedral cordoned off and crumbling, and the Avon River polluted and winding its way in and out of the central city red zone, a severe dissonance existed between the way the city had been known and represented and the reality on the ground. At this early stage in the recovery process, it was important for those in power to address how Christchurch had changed, and the effect this was having on perceptions of the city as both a place to live and a place to visit. The implication of this dissonance was that the identity of the city was up for grabs, and the Share an Idea campaign was trying to shift the brand narrative of the city; it was an early chance for the CCC to convey a message of both stability and opportunity against the backdrop of a central city effectively destroyed by a natural disaster.

Given this context, Share an Idea can be seen as a sort of covert rebrand, as opposed to a simple crowdsourcing campaign. As much as it was about pegging down grand ideas of future cities flying around in the heads of its residents, this was an exercise in brand perception. Share an Idea was asking what Christchurch looks like post-earthquake, and answering the question at the same time: a place where the people are listened to, and where new cities are designed collectively by those who will live in them.

A sense of control

‘The concept of network power reveals complexities in the connection between the idea of consent and the idea of freedom …. A standard is pushed toward universality, and its network becomes poised to merge with the population itself. It is “pushed” by the activity of people evaluating consequences and, ultimately, choosing to adopt a dominant standard because of the access it allows them to forms of cooperation with others.’3

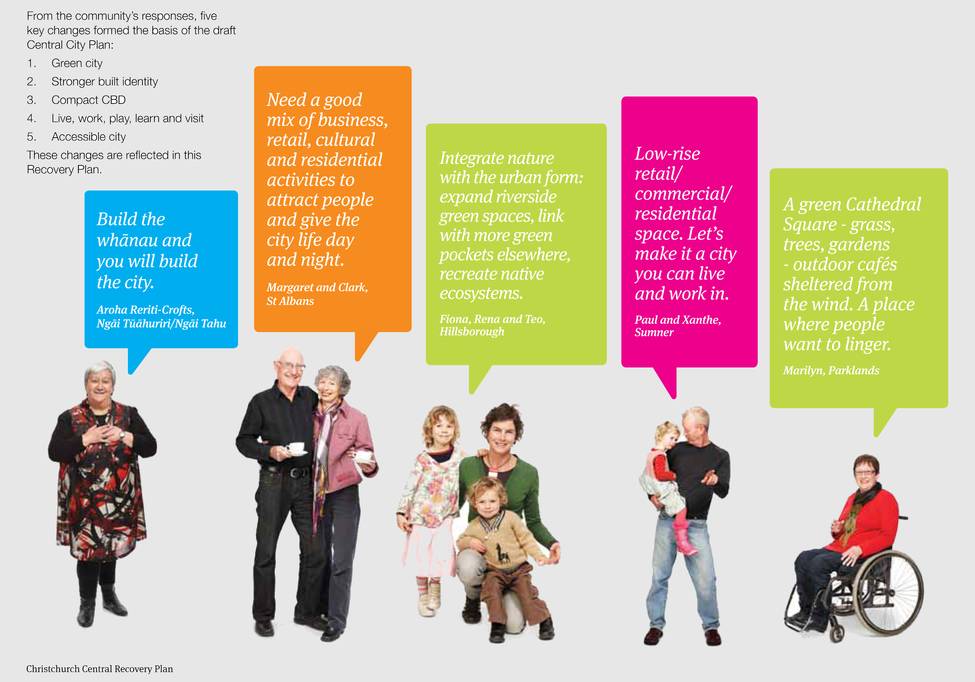

Share an Idea could also be seen as an exercise in network power, where a feeling of public consensus is gained through notions of collective responsibility; people choose to agree because of the inherent sociability this permits. By painting a picture of democratic process, the CCC was able to subtly sell a brand of governance and assert a level of control over outcomes of the campaign through obtaining consent and buy-in from its citizens. The visual language of the campaign reinforced these concepts. The speech bubble design, which forms the central motif of the brand, overtly signifies freedom of thought and opinion. Building from this starting point the design implies vibrancy, youth and diversity through a layered, multi-coloured arrangement, giving the effect of many voices stacked upon each other, collecting together into new forms, and new conversations. As the campaign developed, and ideas were shared, this common theme of a collective voice, and the power of that voice, was continually reinforced and built upon. In conjunction, pictures of real people grounded these visual concepts. Christchurch residents who contributed ideas were paired with speech bubbles that hovered over their heads, each idea given a face, a name and even the suburb where it hailed from (Fig 3).

Figure 3 - From inside the Christchurch Central Recovery Plan

This imagery of real people alongside their ideas for a new Christchurch was employed throughout the CCC’s Draft Central City Recovery Plan, which was presented to Minister for Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Gerry Brownlee who—according to the legislation that created his ministry—was granted unprecedented powers; including the right to ‘direct’ and ‘specify … any changes to the draft recovery plan that he thinks fit’. In fact, he did set aside much of the CCC plan and public consultation, directing a new central government unit to create an implementation plan in 100 days. Through this action, the democratic process and perception of power that Share an Idea promoted has been severely undermined. Despite this, the original speech bubble motif has continued to be used and expanded.

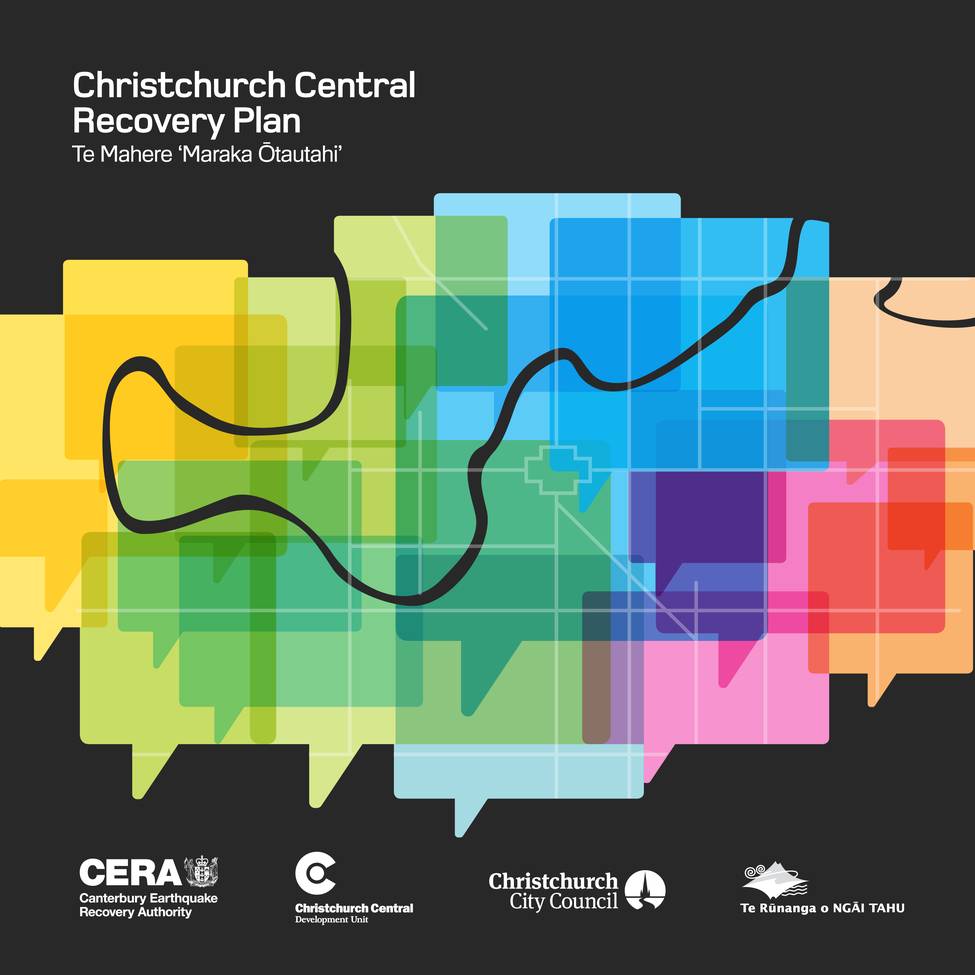

On the cover of the central government’s 100-day plan, the Christchurch Central Recovery Plan (CCRP), numerous multi-coloured speech bubbles of different shapes and sizes overlap one another and are placed on top of the Avon River and central Christchurch streets, creating an abstract visual expression of the city regenerating through word of mouth (Fig 4). In this way, despite the actual process undertaken, the Plan manages to sell both a clear brand message – something new is happening here; and a mode of governance - it’s happening through democratic process.

Figure 4 - The cover image of Christchurch Central Recovery Plan

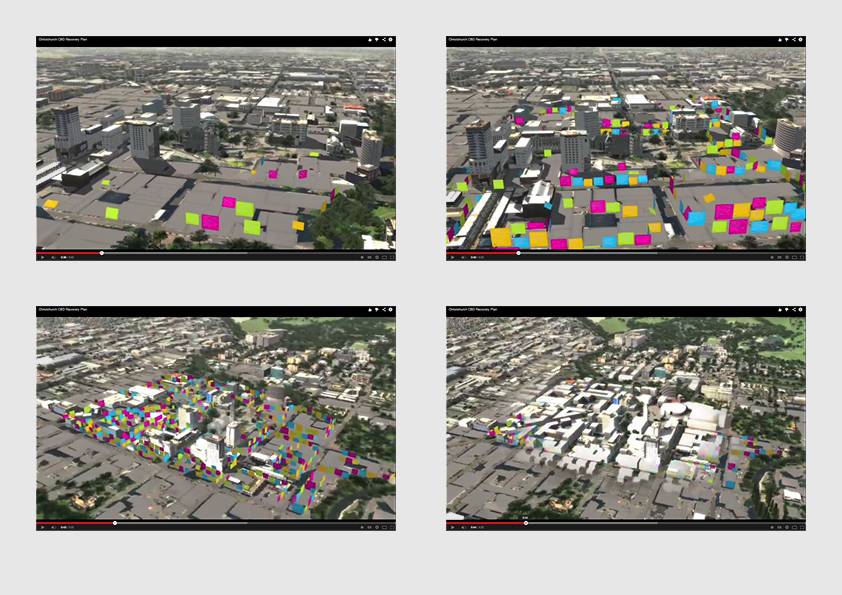

The concept that the ideas being shared were those of actual people – and had real world implications – was continually built upon. The speech bubble motif – at first used as a flat, two-dimensional visual device with which to present content – later began to be represented as a kind of building block. The best example of this use of the device can be found in a promotional video released alongside the central govenrment’s 100-day plan, the CCRP. Supported by a voiceover stating that ‘the people of Christchurch have spoken’, multi-coloured speech bubbles emerge from the rubble of the city centre and stand upright, before further materialising into convention centres, shopping malls, and sports stadiums (Fig 5). Here, the message could not be clearer: the voice of the people, as represented by bright icons of free speech, had been listened to and the shape of the new city had been directly informed by this collective voice. In other words, what was implied through this visualisation was a sense of collective power, achieved not only through ownership of process, but ownership of outcomes.

Figure 5 - Screenshots from a promotional video that supported the release of the Christchurch Central Recovery Plan

What's interesting to consider here, however, is whether any real power actually exchanged hands. Contextualised as an act of network power, Share an Idea was very effective in implying ownership and, as an extension, coercing a level of perceived collective responsibility for the future of the city. But beyond giving the people a positive outlet for ideas, did it actually have any real impact on the bricks and mortar reality of future developments? Any power that was granted through this process was quickly diluted as the number of participants grew and the ideas shared ‘pushed toward universality’,4 the majority of them simply reinforcing the status quo. The obviousness and conservative nature of the crowdsourced opinions acted as a stamp of approval for the preconceived ideas likely held by those in power. Of course people want more green spaces, bike lanes, cultural events and better public transport, and so of course that wasn't really the point of all this. This begins to point toward the futility of the exercise as actual idea generation, and towards the value of Share an Idea as an attempt to soft sell concepts of change, through the veil of democratic process. To lessen the burden of having to sell a new city plan to its citizens, the CCC – through the campaign’s ability to imply the idea of consent and freedom – was seemingly employing the people to sell it back to themselves.

This becomes especially dubious when coupled with the extreme executive power now wielded by the new government ministry, with Brownlee using the same visual language to represent his altered plan – perhaps an attempt to cash in on Share an Idea’s use of symbolism to imply democratic design, decision making, and ultimately power. But with this process a far cry from what was originally on offer, all this has achieved is an ever-widening gap between the message and the messenger.